- Home

- Barbara Pym

Jane and Prudence

Jane and Prudence Read online

JANE AND PRUDENCE

__________

BARBARA PYM

PERENNIAL LIBRARY

Harper & Row, Publishers, New York

Cambridge, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Washington London, Mexico City, Sao Paulo, Singapore, Sydney This book was first published in the United Kingdom in 1953. A hardcover edition was published in the United States in 1981 by Elsevier-Dutton Publishing Co., Inc. It is here reprinted by arrangement with Elsevier-Dutton Publishing Co., Inc.

Jane and Prudence. Copyright 1981 by The Estate of Barbara Pym. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Elsevier-Dutton Publishing Co., Inc., 2 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10016. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto.

First perennial library edition published 1984. Reissued in 1987.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pym, Barbara.

Jane and Prudence.

I. Title.

PR6066.Y58J3 1987 813’.54 86-46097

ISBN 0-06-097101-0 (pbk.)

87 88 89 90 91 MPC 10 987654321

Chapter One

JANE AND PRUDENCE were walking in the college garden before dinner. Their conversation came in excited little bursts, for Oxford is very lovely in midsummer, and the glimpses of grey towers through the trees and the river at their side moved them to reminiscences of earlier days.

‘Ah, those delphiniums,’ sighed Jane. ‘I always used to think Nicholas’s eyes were just that colour. But I suppose a middle-aged man—and he is that now, poor darling I can’t have delphinium-blue eyes.’

‘Those white roses always remind me of Laurence,’ said Prudence, continuing on her own line. ‘Once I remember him coming to call for me and picking me a white rose — and Miss Birkinshaw saw him from her window! It was like Beauty and the Beast,’ she added. ‘Not that Laurence was ugly. I always thought him rather attractive.’

‘But you were certainly Beauty, Prue,’ said Jane warmly. ‘Oh, those days of wine and roses! They are not long.’

‘And to think that we didn’t really appreciate wine,’ said Prudence. ‘How innocent we were then and how happy!’

They walked on without speaking, their silence paying a brief tribute to their lost youth.

Prudence Bates was twenty-nine, an age that is often rather desperate for a woman who has not yet married. Jane Cleveland was forty-one, an age that may bring with it compensations unsuspected by the anxious woman of twenty-nine. If they seemed an unlikely pair to be walking together at a Reunion of Old Students, where the ages of friends seldom have more than a year or two between them, it was because their relationship had been that of tutor and pupil. For two years, when her husband had had a living just outside Oxford, Jane had gone back to her old college to help Miss Birkinshaw with the English students, and it was then that Prudence had become her pupil and remained her friend. Jane had enjoyed those two years, but then they had moved to a suburban parish, and now, she thought, glancing round the table at dinner, here I am back where I started, just another of the many Old Students who have married clergymen. She seemed to see the announcement in the Chronicle under Marriages, ‘Cleveland-Bold’, or, rather, ‘Bold-Cleveland’, for here the women took precedence; it was their world, the husbands existing only in relation to them: ‘Jane Mowbray Bold to Herbert Nicholas Cleveland.’ And later, after a suitable interval, ‘To Jane Cleveland (Bold), a daughter (Flora Mowbray)’.

When she and Nicholas were engaged Jane had taken great pleasure in imagining herself as a clergyman’s wife, starting with Trollope and working through the Victorian novelists to the present-day gallant, cheerful wives, who ran large houses and families on far too little money and sometimes wrote articles about it in the Church Times. But she had been quickly disillusioned. Nicholas’s first curacy had been in a town where she had found very little in common with the elderly and middle-aged women who made up the greater part of the congregation. Jane’s outspokenness and her fantastic turn of mind were not appreciated; other qualities which she did not possess and which seemed impossible to acquire were apparently necessary. And then, as the years passed and she realised that Flora was to be her only child, she was again conscious of failure, for her picture of herself as a clergyman’s wife had included a large Victorian family like those in the novels of Miss Charlotte M. Yonge.

‘At least I have had Flora, even though everybody else here has at least two children,’ she said, speaking her thoughts aloud to anybody who happened to be within earshot.

‘I haven’t,’ said Prudence a little coldly, for she was conscious on these occasions of being still unmarried, though women of twenty-nine or thirty or even older still could and did marry judging by other announcements in the Chronicle. She wished Jane wouldn’t say these things in her rather bright, loud voice, the voice of one used to addressing parish meetings. And why couldn’t she have made some effort to change for dinner instead of appearing in the baggy-skirted grey flannel suit she had arrived in? Jane was really quite nice-looking, with her large eyes and short, rough, curly hair, but her clothes were terrible. One could hardly blame people for classing all university women as frumps, thought Prudence, looking down the table at the odd garments and odder wearers of them, the eager, unpainted faces, the wispy hair, the dowdy clothes; and yet most of them had married—that was the strange and disconcerting thing.

Prudence looks lovely this evening, thought Jane, like somebody in a woman’s magazine, carefully ‘groomed’, and wearing a red dress that sets off her pale skin and dark hair. It was odd, really, that she should not yet have married. One wondered if it was really better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all, when poor Prudence seemed to have lost so many times. For although she had been, and still was, very much admired, she had got into the way of preferring unsatisfactory love affairs to any others, so that it was becoming almost a bad habit. The latest passion did not sound any more suitable than her previous ones. Something to do with her work, Jane believed, for she had hardly liked to ask for details as yet. The details would assuredly come out later that evening, over what used to be cocoa or Ovaltine in one of their bed—sitting-rooms when they were students and would now be rather too many cigarettes without the harmless comfort of the hot drink.

‘So you have all married clergymen,’ said Miss Birkinshaw in a clear voice from her end of the table. ‘You, Maisie, and Jane and Elspeth and Sybil and Prudence . .’

‘No, Miss Birkinshaw,’ said Prudence hastily. ‘I haven’t married at all.’

‘Of course, I remember now — you and Eleanor Hitchens and Mollie Holmes are the only three in your year who didn’t marry.’

‘You make it sound dreadfully final,’ said Jane. ‘I’m sure there is hope for them all yet.’

‘Well, Eleanor has her work at the Ministry, and Mollie the Settlement and her dogs, and Prudence, her work, too.. ‘ Miss Birkinshaw’s tone seemed to lose a little of its incisiveness, for she could never remember what it was that Prudence was doing at any given moment. She liked her Old Students to be clearly labelled — the clergymen’s wives, the other wives, and those who had ‘fulfilled’ themselves in less obvious ways, with novels or social work or a brilliant career in the Civil Service. Perhaps this last could be applied to Prudence? thought Miss Birkinshaw hopefully.

She might have said, ‘and Prudence has her love affairs’, thought Jane quickly, for they were surely as much an occupation as anything else.

‘Your work must be very interesting, Prudence, ‘ Miss Birkinshaw went on. ‘I never like to

ask people in your position exactly what it is that they do. ‘

‘I’m a sort of personal assistant to Dr. Grampian, ‘ said Prudence. ‘It’s rather difficult to explain. I look after the humdrum side of his work, seeing books through the press and that kind of thing. ‘

‘It must be wonderful to feel that you have some part, however small, in his work,’ said one of the clergymen’s wives.

‘I dare say you write quite a lot of his books for him,’ said another. ‘I often think work like that must be ample compensation for not being married,’ she added in a patronising tone.

‘I don’t need compensation,’ said Prudence lightly. ‘I often think being married would be rather a nuisance. I’ve got a nice flat and am so used to living on my own I should hardly know what to do with a husband.’

Oh, but a husband was someone to tell one’s silly jokes to, to carry suitcases and do the tipping at hotels, thought Jane, with a rush. And although he certainly did these things, Nicholas was a great deal more than that.

‘I like to think that some of my pupils are doing academic work,’ said Miss Birkinshaw a little regretfully, for so few of them did. Dr. Grampian was some kind of an economist or historian, she believed. He wrote the kind of books that nobody could be expected to read.

‘Here we are all gathered round you,’ said Jane, ‘and none of us has really fulfilled her early promise.’ For a moment she almost regretted her own stillborn ‘research’ — ‘the influence of something upon somebody’ hadn’t Virginia Woolf called it? — to which her early marriage had put an end. She could hardly remember now what the subject of it was to have been — Donne, was it, and his influence on some later, obscurer poet? Or a study of her husband’s namesake, the poet John Cleveland? When they had got settled in the new parish to which they were shortly moving she would dig out her notes again. There would be much more time for one’s own work in the country.

Miss Birkinshaw was like an old ivory carving, Prudence thought, ageless, immaculate, with lace at her throat. She had been the same to many generations who had studied English Literature under her tuition. Had she ever loved? Impossible to believe that she had not, there must surely have been some rather splendid tragic romance a long time ago — he had been killed or died of typhoid fever, or she, a new woman enthusiastic for learning, had rejected him in favour of Donne, Marvell and Carew.

Had we but World enough, and Time

This Coyness Lady were no crime …

But there was never world enough nor time and Miss Birkinshaw’s great work on the seventeenth-century metaphysical poets was still unfinished, would perhaps never be finished. And Prudence’s love for Arthur Grampian, or whatever one called it — perhaps love was too grand a name — just went hopelessly on while time slipped away….

‘Now, Jane, I believe your husband is moving to a new parish,’ said Miss Birkinshaw, gathering the threads of the conversation together. ‘I saw it in the Church Times. You will enjoy being in the country, and then there is the cathedral town so near.’

‘Yes, we are going in September. It will all be like a novel by Hugh Walpole,’ said Jane eagerly.

‘Unfortunately, it is rather a modern cathedral,’ said one of the clerical wives, ‘and there is one of the canons I do not care for myself.’

‘But I’ve never thought of myself as caring for canons,’ said Jane rather wildly.

‘One woman’s canon might be another woman’s …’ began another clerical wife, but her sentence trailed off unhappily, giving an effect almost of impropriety which was not made any better by Jane saying gaily, ‘I can promise you there will be nothing like that!’

‘It is an attractive little place you are going to,’ said Miss Birkinshaw. ‘Perhaps it has grown since I last saw it, when it was hardly more than a village.’

‘I believe it is quite spoilt now,’ said somebody eagerly. ‘Those little places near London are hardly what they were.’

‘Well, I expect it will be better than the suburbs,’ said jane. ‘People will be less narrow and complacent.’

‘Your husband will have to go carefully,’ said a clerical wife. ‘We had great difficulties, I remember, when we moved to our village. The church was not really as Catholic as we could have wished, and the villagers were very stubborn about accepting anything new.’

‘Oh, we shall not attempt to introduce startling changes,’ said Jane. ‘There is a nearby church quite newly built where all that has been done. The vicar was up here at the same time as my husband.’

‘And we are to have your daughter Flora with us, next term,’ said Miss Birkinshaw. ‘I always like to see the children coming along.’

‘Ah, yes; I shall live my own Oxford days over again with her,’ sighed Jane.

There was a scraping of chairs and then silence. Miss Jellink, the Principal, had risen. The assembled women bowed their heads for grace. ‘Benedicto henedicatur,’ pronounced Miss Jellink in a thoughtful tone, as if considering the words.

There was coffee in the Senior Common Room and then chapel in the little tin-roofed building among the trees at the bottom of the garden. Jane sang heartily, but Prudence was silent beside her. The whole business of religion was meaningless to her, but there was a certain comfort even in the reedy sound of un-trained women’s voices raised in an evening hymn. Perhaps it was because it took her back to her college days, when love, even if sometimes unrequited or otherwise unsatisfactory, tended to be so under romantic circumstances, or in the idyllic surroundings of ancient stone walls, rivers, gardens, and even the reading-rooms of the great libraries.

After chapel there was more walking in the gardens until dusk and then much gathering in rooms for gossip and confidences.

Jane ran to her window and looked out at the “river and a tower dimly visible through the trees. She had been given the room she had occupied in her third year and the view was full of memories. Here she had seen Nicholas coming along the drive on his bicycle, little dreaming that he was to become a clergyman — though, seeing him standing in the hall with his bicycle clips still on, perhaps she should have realised that he was bound to be a curate one day. She could remember him so vividly, wheeling his bicycle along the drive, with his fearful upward glance at her window, almost as if he were afraid that Miss Jellink and not Jane herself would be looking out.

Prudence had her memories too. Laurence and Henry and Philip, so many of them, for she had had numerous admirers, all coming up the drive, in a great body, it seemed, though in fact they had come singly. If she had married Henry, now a lecturer in English at a provincial university, Prudence thought, or Laurence, something in his father’s business in Birmingham, or even Philip, small and spectacled and talking so earnestly and boringly about motor cars … but Philip had been killed in North Africa because he knew all about tanks…. Tears, which she had never shed for him when he was alive, now came into Prudence’s eyes.

‘Poor Prue,’ said Jane rather heartily, wondering what she could say. Who was she weeping for now? Could it be Dr. Grampian? ‘But after all, he is married, isn’t he?—I mean there is a wife somewhere even if you’ve never met her. You shouldn’t really consider him as a possibility, you know. Unless she were to die, of course, that would be quite all right’ A widower, that was what was needed if such a one could be found. A widower would do splendidly for Prudence.

‘I was thinking about poor Philip,’ said Prudence rather coldly.

‘Poor Philip?’ Jane frowned. She could not remember that there had ever been anyone called Philip. ‘Which, who … ?’ she began.

‘Oh, you wouldn’t remember,’ said Prudence lighting another cigarette. ‘It just reminded me, looking out at this view, but really I haven’t thought about him for years.’

‘No, I suppose Adrian Grampian is the one now,’ said Jane.

‘His name isn’t Adrian; it’s Arthur.’

‘Arthur; yes, of course.’ Could one love an Arthur? Jane wondered. Well, all things were possible. Sh

e began to think of Arthurs famous in history and romance — the Knights of the Round Table of course sprang to mind immediately, but somehow it wasn’t a favourite name in these days; there was a faded Victorian air about it.

‘It isn’t so much what there is between us as what there isn’t,’ Prudence was saying; ‘it’s the negative relationship that’s so hurtful, the complete lack of rapport, if you see what I mean.’

‘It sounds rather restful in a way,’ said Jane, doing the best she could, ‘to have a negative relationship with somebody. Of course a vicar’s wife must have a negative relationship with a good many people, otherwise life would hardly be bearable.’

‘But this isn’t quite the same thing,’ said Prudence patiently. ‘You see underneath all this, I feel that there really is something, something positive….’

Jane swallowed a yawn, but she was fond of Prudence and was determined to do what she could for her. When they got settled in the new parish she would ask her to stay, not just for a week-end, but for a nice long time. New surroundings and new people would do much for her and there might even be work she could do, satisfying work with her hands, digging, agriculture, something in the open air. But a glance at Prudence’s small, useless-looking hands with their long red nails convinced her that this would hardly be suitable. Not agriculture then, but a widower, that was how it would have to be.

Chapter Two

‘I FEEL THAT a crowd of our new parishioners ought to be coming up the drive to welcome us,’ said Jane, looking out of the window over the laurel bushes, ‘but the road is quite empty.’

‘That only happens in the works of your favourite novelist,’ said her husband indulgently, for his wife was a great novel reader, perhaps too much so for a vicar’s wife. ‘It’s really better to get settled in before we have to deal with people. I told Lomax to come round after supper, perhaps for coffee.’ He looked up at his wife hopefully.

Crampton Hodnet

Crampton Hodnet Quartet in Autumn

Quartet in Autumn No Fond Return of Love

No Fond Return of Love The Sweet Dove Died

The Sweet Dove Died Excellent Women

Excellent Women A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym

A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym Jane and Prudence

Jane and Prudence A Glass of Blessings

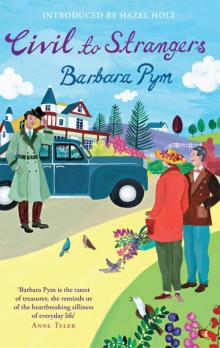

A Glass of Blessings Civil to Strangers and Other Writings

Civil to Strangers and Other Writings An Unsuitable Attachment

An Unsuitable Attachment Less Than Angels

Less Than Angels A Few Green Leaves

A Few Green Leaves Civil to Strangers

Civil to Strangers