- Home

- Barbara Pym

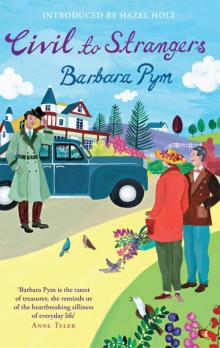

Civil to Strangers and Other Writings

Civil to Strangers and Other Writings Read online

VIRAGO

MODERN CLASSICS

556

Barbara Pym

Barbara Pym (1913–1980) was born in Oswestry, Shropshire. She was educated at Huyton College, Liverpool, and St Hilda’s College, Oxford, where she gained an Honours Degree in English Language and Literature. During the war she served in the WRNS in Britain and Naples. From 1958–1974 she worked as an editorial secretary at the International African Institute. Her first novel, Some Tame Gazelle, was published in 1950, and was followed by Excellent Women (1952), Jane and Prudence (1953), Less than Angels (1955), A Glass of Blessings (1958) and No Fond Return of Love (1961).

During the sixties and early seventies her writing suffered a partial eclipse and, discouraged, she concentrated on her work for the International African Institute, from which she retired in 1974 to live in Oxfordshire. A renaissance in her fortunes came in 1977, when both Philip Larkin and Lord David Cecil chose her as one of the most underrated novelists of the century. With astonishing speed, she emerged, after sixteen years of obscurity, to almost instant fame and recognition. Quartet in Autumn was published in 1977 and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. The Sweet Dove Died followed in 1978, and A Few Green Leaves was published posthumously. Barbara Pym died in January 1980.

Also by Barbara Pym

Some Tame Gazelle

Excellent Women

Less than Angels

A Glass of Blessings

No Fond Return of Love

Quartet in Autumn

The Sweet Dove Died

A Few Green Leaves

Crampton Hodnet

An Unsuitable Attachment

An Academic Question

Jane and Prudence

COPYRIGHT

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-0-748-12810-5

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 1987 by Barbara Pym

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

www.hachette.co.uk

CONTENTS

Virago Modern Classics 556

Also by Barbara Pym

Copyright

Introduction by Hazel Holt

PART ONE: CIVIL TO STRANGERS

Civil to Strangers

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

PART TWO: FINDING A VOICE

Gervase and Flora

Gervase and Flora

Home Front Novel

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

So Very Secret a spy novel

So Very Secret

Short Stories

So, Some Tempestuous Morn

Goodbye Balkan Capital

The Christmas Visit

Across a Crowded Room

Finding a Voice: a radio talk

Excellent Women

A Glass of Blessings

INTRODUCTION

When A Last Sheaf was published, several years after Denton Welch’s death, Barbara Pym wrote, ‘How splendid that we are to be given one more Denton.’ When she died in 1980 she left not only nine published novels, but also a considerable amount of unpublished material. So I gathered together Barbara’s own last sheaf, a final selection from her unpublished writings.

Barbara Pym was from a generation that disliked waste and was naturally frugal: she made over her old clothes (letting in bands of different colours to achieve a newly fashionable hemline) and devised delicious meals from leftovers. She was equally thrifty in her work. Characters from her early, unpublished work appear in later novels (for example, Miss Morrow and Miss Doggett from Crampton Hodnet are later found in Jane and Prudence, as well as in the short story ‘So, Some Tempestuous Morn’), and when she was unable to find a publisher for An Unsuitable Attachment, she salvaged Mark and Sophia Ainger and, especially, Faustina for use in ‘The Christmas Visit’. So I am sure she would be pleased that so much of her work that wasn’t published in her lifetime is available to be read and enjoyed.

From the beginning of her career as a published novelist in 1950 (though she had been writing novels since the age of sixteen), she had consistently good reviews. John Betjeman described her, in 1952, as ‘a splendidly humorous writer’ and the chorus of praise grew with each new book until her later novels were best-sellers here and in the United States where she had a growing following. The novelist Anne Tyler wrote, ‘Whom do people turn to when they’ve finished Barbara Pym? The answer is easy; they turn back to Barbara Pym,’ and John Updike in the New Yorker wrote of her novels: ‘A startling reminder that solitude may be chosen and that a lively, full novel can be constructed entirely within the precincts of that regressive virtue, feminine patience.’ Best of all was her champion Philip Larkin’s assertion that he’d ‘sooner read a new Barbara Pym than a new Jane Austen’. In 1977 she was on the shortlist for the Booker Prize for Quartet in Autumn (even more prestigious then, when there were few literary awards) and received the popular accolade of appearing on Desert Island Discs.

This late success was especially heartening as she had previously had such a blow to her confidence. When Jonathan Cape rejected An Unsuitable Attachment in 1963, Barbara tried to place it with other publishers, but in the 1960s her novels were thought to be old fashioned. As one publisher remarked, it was ‘not the sort of book to which people were turning’. There followed fourteen years of rejection and frustration until, in 1977, the Times Literary Supplement published a list, chosen by eminent literary figures, of the most underrated writers of the century. Barbara was the only living writer chosen by two people: Lord David Cecil and Philip Larkin. She was deemed publishable again.

After her death in 1980 she left behind complete but unpublished novels, half-finished works, short stories and a mass of papers – especially diaries and the series of notebooks where she had noted down odd thoughts, comments, overheard remarks and ideas for novels. It seemed, given the interest her novels had aroused, suitable to publish the latter. A Very Private Eye: An Autobiography in Diaries and Letters (published in 1984) caused a minor publishing sensation, giving, as it did, a fuller, and unexpected, picture of her very varied life. It was received with enthusiasm and there seemed to be a desire for ‘more Barbara Pym’. An Unsuitable Attachment had finally been published in 1982 and received good reviews here and ecstatic ones in the United States: the Washington Post commented, ‘The publisher must have been mad to reje

ct this jewel. The cut-glass elegance of her precise understated wit sparkles, her understanding of the human heart gleams more softly but just as bright’ and the New Yorker called it ‘a paragon of a novel’. Then Crampton Hodnet was published in 1985 and An Academic Question followed in 1986.

Civil to Strangers, which appeared in 1987, was the result of requests from the many scholars writing about her novels, who wanted access to her earlier work, but which also proved very popular with all her non-academic readers.

The novel at the centre of this collection was written in 1936, when she was twenty-three, and has all the confidence of youth. She greatly admired the novels of Elizabeth von Arnim, especially The Enchanted April, and she seems to have made it the springboard, as it were, for this book. There are several parallels: the selfish, uncaring husband, the apparently submissive wife who, nevertheless, observes life with an ironic eye, and the transformation of a difficult husband by the Romance of Abroad. The style has something of the same cadence – formal, light, elegant, slightly sardonic. But Barbara could never be just an imitator and her own personality comes through early on. Then there are the purely Pym characters: the Rector and his family, Mr Paladin the curate, as well as the splendid Mrs Gower – and no one but Barbara could have written chapter thirteen. This novel is interesting too because it is one of the few in which the heroine goes abroad, and the passages set in pre-war Budapest have the charm and interest of descriptions of a vanished world.

The second half of this book is a collection of novels and short stories, mostly written while she was living at home in Oswestry before or during the war, which show how Barbara was working steadily at her craft. I also included the radio talk she gave, Finding a Voice, in 1978. It was part of a series featuring well-known writers (the author before her had been Beryl Bainbridge) on how they developed their own individual style. She was very pleased to be asked to contribute, since it was a confirmation at last of her position as a professional writer, a title especially precious after her years in the literary wilderness. Reading this piece is poignant since we can hear her quiet, rather hesitant voice, summing up with style and succinctness, her thoughts on writing and on ‘finding one’s own particular voice’, ending, typically, on a wry, almost wistful query.

So often, after well-known novelists die, their reputation, high in their lifetime, diminishes over the years. With Barbara, the opposite has happened. Since Civil to Strangers, the last of her posthumously issued books, was first published, her reputation has grown. This is most satisfactory, though it is sad to think that, after her rediscovery in 1977, she only enjoyed three years of her hard-won success.

It is remarkable to see how many editions of Barbara Pym’s books there have been. In addition, she has been translated into French, Italian, German, Dutch, Portuguese, Hungarian, Russian and Japanese and there are to be new editions published shortly in Italian and Spanish. So it still goes on and all her novels remain in print. A number of books about her work have been published and there seem to be more to come. And she would be delighted to know that she has provided a rich field for students (not all like Larkin’s Jake Balokowski) looking for a worthy subject for a thesis, many of whom come to visit the collection of Pym papers in the Bodleian library. Towards the end of her life, Barbara said, with a mixture of pleasure and incredulity, ‘I am being taught in Texas!’ She would be amazed and gratified to know that she still provides material for English literature courses (mostly in America). There are two flourishing Barbara Pym Societies, the main English branch based on Barbara’s old college, St Hilda’s in Oxford, and the American one in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Both hold annual conferences, both well attended and with distinguished speakers, and they both include a dramatised reading, each time, of one of Barbara’s unpublished works.

Once, when she was unpublished and depressed, she wrote to Philip Larkin, ‘Here I am sixty-one (it looks worse spelled out in words) and only six novels published – no husband, no children’, to which Philip replied sharply, ‘Didn’t J. Austen write six novels, and not have a husband and children?’ – not the first comparison with Jane Austen, but one of the best. The fact is that all Barbara wanted to be was a writer, that was the main-spring of her life. ‘After supper,’ she wrote in her diary in 1941, ‘I did some more writing which quells my restlessness – that is how I must succeed!’ She could have had a husband and children (she rejected several proposals of marriage) but the men she really cared for had married other people. As she moved towards her maturity as a writer she looked back on her relationships – recollection, not in tranquillity precisely, but with an amused and affectionate compassion. She knew she could transmute them, by the alchemy that is creativity, into Material, the aim of every writer.

Even though she had such a short time of personal success, she did achieve what she always wanted. That magic year of 1977 she wrote in her notebook, ‘Who is that woman sitting on the concrete wall outside Barclay’s Bank reading the TV Times? That is Miss Pym the novelist.’ No one else could have written that. At the end of her radio talk, Finding a Voice, published in this volume, she sums it all up: ‘I think that’s the kind of immortality most authors would want – to feel that their work would be immediately recognisable as having been written by them and by nobody else.’ And she adds, in her typically self-effacing way, ‘But, of course, it’s a lot to ask for!’

But that is the kind of immortality she has achieved. Her voice is immediately recognisable; that word includes the whole person – what she thought, believed in and, especially, noticed. Her work is still read not only for the style but for what it says to us, now, as we read it. One of the most remarkable things is the way her name has become a sort of shorthand for a certain kind of person, moment or, even, place. It crops up regularly (sometimes in the most unexpected places) in books, on the radio and television. Truly, as the novelist Shirley Hazzard has said: ‘We may now say Barbara Pym and be understood instantly.’ ‘To say that a moment is “very Barbara Pym”’, Alexander McCall Smith writes, ‘is to say that it is a self-observed, poignant acceptance of the modesty of one’s circumstances, of one’s peripheral position.’

It would seem that we are still glad to turn to the author who advocated small, blameless pleasures, to provide us with good books for a bad day.

Hazel Holt, 2011

PART ONE

Civil to Strangers

Civil to Strangers

‘Her Conduct Regular, her Mirth Refin’d,

Civil to Strangers, to her Neighbours kind’

John Pomfret, The Choice

Note on the Text

This was Barbara’s second novel (362 pages), written in 1936, after the first version of Some Tame Gazelle had gone the rounds of the publishers with no success.

In May she wrote to Henry Harvey, ‘Did I tell you I had started a new novel? I am just beginning to get it into form, although at first I found it something of an effort.’ By July 17th she had got as far as Chapter 6 and on the 20th she noted, ‘Today I wrote about 8 pages in a large foolscap size notebook. I’d like if possible to get the whole thing done by November. It will be something to work for.’ On August 20th she wrote to Henry Harvey:

Adam and Cassandra are getting on quite nicely though I haven’t done much to them lately. Adam is sweet but very stupid. You are sweet too, but not as consistently stupid as Adam. But I wish you were here to show me where to put commas and to help me with my novel … I am all alone in the house, except for the wireless, which you despise so much. I am writing rather slowly and laboriously and every time I think of something nice to say I stop and consider it well before I put it in.

In October she was revising and typing (on the Remington portable her father had just given her): ‘In the morning I finished (typing) Chapter XIV of Adam and Cassandra [the original title]. I have now reached p.170 and think I can finish it. It seems to get better as it goes on, I think.’

The later part of the book, set in Hungary, was inspired

by Barbara’s own visit in August 1935, when she and her sister Hilary went to Budapest with a group from the National Union of Students. As always she had a lively time, with many admirers.

Civil to Strangers marks a turning point in Barbara’s development. The confident but slightly self-indulgent enthusiasm of the first draft of Some Tame Gazelle has been tempered with maturity of style and craftsmanship. Barbara Pym the writer was turning into Barbara Pym the novelist.

Note: the quotations at the beginning of each chapter are all taken from James Thomson’s poem ‘The Seasons’.

CHAPTER ONE

‘’Tis silence all,

And pleasing expectation.’

‘Dear Cassandra,’ smiled Mrs Gower, ‘you are always so punctual.’ She leaned forward, and brushed Cassandra’s cheek with her lips. Cassandra responded with a similar gesture, a little awkwardly, for Mrs Gower was a large woman, and her cheek was rather difficult to reach.

‘I always try to be punctual,’ said Cassandra with a smile, although the flat, even tone of her voice implied that she had made the remark many times before.

‘You have every virtue, my dear,’ said Mrs Gower warmly, as they settled themselves on the sofa.

Cassandra sighed, although not loudly enough for Mrs Gower to hear. She knew that she had every virtue, because people were always telling her so. She was twenty-eight years old, a tall, fair young woman, not exactly pretty, but comely and dignified. This afternoon she was wearing a well-cut costume of blue tweed. Her hat and shoes were sensible rather than fashionable. Cassandra could always be relied upon never to wear anything unsuitable to the place she happened to be in at the time.

‘I asked Mrs Wilmot and Janie to come this afternoon,’ said Mrs Gower. ‘I suppose you didn’t see any sign of them as you came past the rectory?’

Crampton Hodnet

Crampton Hodnet Quartet in Autumn

Quartet in Autumn No Fond Return of Love

No Fond Return of Love The Sweet Dove Died

The Sweet Dove Died Excellent Women

Excellent Women A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym

A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym Jane and Prudence

Jane and Prudence A Glass of Blessings

A Glass of Blessings Civil to Strangers and Other Writings

Civil to Strangers and Other Writings An Unsuitable Attachment

An Unsuitable Attachment Less Than Angels

Less Than Angels A Few Green Leaves

A Few Green Leaves Civil to Strangers

Civil to Strangers