- Home

- Barbara Pym

Crampton Hodnet

Crampton Hodnet Read online

Copyright 1985 by Hilary Walton All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A.

Published in the United States by E. P. Dutton, 2 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Pym, Barbara. Crampton Hodnet. I. Title.

PR6066.Y58C7 198; 823’. 914 85-1467 ISBN 0-525-24333-X

Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto

DESIGNED BY MARK O’CONNOR

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

NOTE

Barbara Pym began Crampton Hodnet just after the outbreak of war in 1939. In spite of wartime tasks, housework and evacuees, it progressed steadily:

“18 Nov. 1939: Did about 8 pages of my novel. It grows very slowly and is rather funny I think — 22 Dec. 1939: Determined to finish my N. Oxford novel and send it on the rounds.”

In January 1940 she wrote to her friend Robert Liddell:

“I am now getting into shape the novel I have been writing during this last year. It is about North Oxford and has some bits as good as anything I ever did. Mr. Latimer’s proposal, old Mrs. Killigrew, Dr. Fremantle, Master of Randolph College, Mr. Cleveland’s elopement and its unfortunate end … I am sure all these might be a comfort to somebody.“

The novel was completed and sent to Robert Liddell in April. But before she could send it “on the rounds” she became more deeply involved in war work and the novel was laid aside.

After the war she looked at it again and made some revisions and alterations, but it seemed to her to be too dated to be publishable. Instead, she concentrated on revising the more timeless Some Tame Gazelle, and the manuscript of Crampton Hodnet remained among her other unpublished works. Now, for readers in 1985, the period quality adds an extra dimension to the novel.

Crampton Hodnet is one of Barbara’s earliest completed novels, and in it she was still feeling her way as a writer. Occasional over-writing and over-emphasis led to repetition, which, in preparing the manuscript for press, I have tried to eliminate. I was greatly helped by Barbara’s own emendations (made in the 1950s) and by some notes she made about this novel in her pocket-diary for 1939.

Faithful readers of the novels will welcome the first incarnation of Miss Doggett and Jessie Morrow. It is interesting to see how, in Jane and Prudence, she redraws them from a more ironic and more subtle point of view. And it is not impossible that the young Barbara Bird of Crampton Hodnet might have grown into the brusque novelist of the later work.

Barbara herself lit upon the exact word to describe this book. It is more purely funny than any of her later novels. So far, everyone who has read the manuscript has laughed out loud - even in the Bodleian Library.

Hazel Holt

London, 1985

I. Sunday Tea Party

It was a wet Sunday afternoon in North Oxford at the beginning of October. The laurel bushes which bordered the path leading to Leamington Lodge, Banbury Road, were dripping with rain. A few sodden chrysanthemums, dahlias and zinnias drooped in the flower-beds on the lawn. The house had been built in the sixties of the last century, of yellowish brick, with a gabled roof and narrow Gothic windows set in frames of ornamental stonework. A long red and blue stained-glass window looked onto a landing halfway up the pitch-pine staircase, and there were panels of the same glass let into the front door, giving an ecclesiastical effect, so that, except for a glimpse of unlikely lace curtains, the house might have been a theological college. It seemed very quiet now at twenty past three, and upstairs in her big front bedroom Miss Maude Doggett was having her usual rest. There was still half an hour before her heavy step would be heard on the stairs and her loud, firm voice calling to her companion, Miss Morrow.

It was cold this afternoon, but there would not be a fire in the dining-room until the first of November. A vase of coloured teasels filled the emptiness of the fireplace over which Miss Morrow crouched, listening to the wireless. It was a programme of gramophone records from Radio Luxembourg, and Miss Morrow’s hand was on the switch, ready to fade out this unsuitable noise should the familiar step and voice be heard before their time.

Jessie Morrow was a thin, used-up-looking woman in her middle thirties. She had been Miss Doggett’s companion for five years and knew that she was better off than many of her kind, because she had a very comfortable home and one did at least meet interesting people in Oxford. Undergraduates came every week to Miss Doggett’s Sunday afternoon tea parties, and her nephew, Francis Cleveland, who lived only a few houses away, was a Fellow of Randolph College and a University Lecturer in English Literature.

Miss Morrow, in spite of her misleading appearance, was a woman of definite personality, who was able to look upon herself and her surroundings with detachment. This afternoon, however, she was feeling a little depressed. She shivered and pulled her shapeless grey cardigan round her thin body. She looked out of the window at the dripping monkey-puzzle tree, whose spiky branches effectively kept out any sun there might be. Then, turning back to the wireless, she advanced the volume control so that the music filled the dark North Oxford dining-room and seemed to bring to it some of the warmth and sinful brightness of a continental Sunday. There’s magic in the air said a smooth, lingering voice against a background of rich, indefinite music. Miss Morrow knew this one. It was chocolates, a programme for Lovers. And then suddenly it went scratchy, and she remembered that it was not really a gay continental Sunday she was listening to but a tired, bored young man sitting in a studio somewhere between Belgium and Germany, putting on innumerable gramophone records to advertise all the many products that thoughtful people had invented to help you to attract your man or get your washing done in half the time.

If I had any strength of character, thought Miss Morrow, I should be able to take a wet Sunday afternoon in North Oxford with no fire to sit by in my stride. I might even take a pleasure in its gloominess and curiously Gothic quality. But such pleasures are only for the very sophisticated who can look on them from a distance without being swamped by them every day of their lives. There were one or two young men who enjoyed Miss Doggett’s tea parties and found delight and comfort in the Victorian splendour of her drawing-room, but Miss Morrow did not pretend to be anything more than a woman past her first youth, resigned to the fact that her life was probably never going to be more exciting than it was now. With a sudden twist of her hand she turned off the music. It was degrading to think that she could not take a quiet pride in her resignation and leave it at that. In less than half an hour the undergraduates would begin to arrive, filling the hall with their dripping mackintoshes and umbrellas.

Miss Morrow went quickly upstairs to her large, cold bedroom and put on her dark green marocain dress. The mirror was in an unflattering light. She saw only too clearly her thin neck and small, undistinguished features, her faded blond hair done in a severe knot. There was no time to put powder or a touch of colour on her cheeks for Miss Doggett was already calling her.

‘Miss Morrow! Miss Morrow!’ she called, her voice rising to a shrill note. ‘Where are the buns from Boffin’s? Florence says she can’t find them. You ought to see to these things. Where did you put them?’

‘In the sideboard, in a tin,’ shouted Miss Morrow, struggling with the hooks of her dress.

‘Which tin?’

‘The Balmoral tin.’

‘What? I can’t hear you. Why don’t you come down?’

Miss Morrow rushed out of her room looking rather dishevelled. ‘I mean the tin with the picture of Balmoral on it,’ she explained.

‘Oh, here they are, madam,’ said Florence. ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t look in here.’

‘Well, hurry up! The young men will be arriving soon,’ said Miss Doggett. She was a large, formidable woman of seventy with th

ick grey hair. She wore a purple woollen dress and many gold chains round her neck. Her chief work in life was interfering in other people’s business and imposing her strong personality upon those who were weaker than herself. She pushed past Miss Morrow, who was hovering in the doorway, and entered the drawing-room.

‘The fire has been lit for half an hour,’ she said, glancing swiftly round the room to see that everything was as she liked it. ‘It ought to be quite warm now, but in any case young people don’t feel the cold. Nor would older ones if they wore sensible underclothes,’ she added in a deliberate tone.

Miss Morrow understood the implication. It concerned a cotton vest which had been found among the laundry four years ago. It had been claimed by Miss Morrow.

‘There is no warmth in cotton,’ continued Miss Doggett. We would hardly expect to find warmth in cotton.’

Miss Morrow felt the reassuring tickle of her woollen underwear and turned away to hide a smile.

The big, cold drawing-room, with its Victorian mahogany furniture and air of mustiness which the struggling fire did nothing to dispel, waited to receive the young people. Miss Doggett moved heavily about the room, arranging chairs and putting out the photographs of Italian churches, the dry-looking engravings of Bavarian lakes and the autographed copy of In Memoriam which Lord Tennyson had given to her father, in case any of the young men should be interested in Art.

The bell rang. There was a pause, then the sound of the front door opening and a scuffling in the hall.

Florence announced Mr. Cherry and Mr. Bompas.

Mr. Cherry came, or rather stumbled, into the room. Mr. Bompas, with a whispered ‘You go first’, had pushed him too hard.

‘Ah, the first arrivals,’ said Miss Doggett, making them feel that they had come too early. ‘Your aunt is a very great friend of mine,’ she added, turning to Mr. Bompas.

‘Oh, yes?’ said Mr. Bompas vaguely. He had a great many aunts and was trying to think which one could have been responsible for this invitation. He was short and thick-set, with fair, bristly hair. He was expected to get his Blue for football. Mr. Cherry was thin and mousy with spectacles. He was a thoughtful young man, quite intelligent, but very shy.

Miss Doggett now turned to him. ‘Canon Oke wrote to me about you,’ she said ominously.

‘Canon Oke?’ Mr. Cherry waited uncertainly. What was the vicar of his home parish likely to write about him? he wondered. He believed that it could hardly be anything to his discredit.

Miss Doggett paused and said in an impressive tone, ‘He told me you were a Bolshevik.’

Mr. Cherry was as startled as the others at hearing this violent word, and he was as conscious of its incongruity as applied to himself as he imagined they were. ‘I’m a Socialist,’ he said shyly. ‘I suppose he meant that.’

‘Socialist may have been the word he used,’ said Miss Doggett, ‘but I really see no difference between the two.’

‘Oh, yes?’ How silly that one couldn’t think of a more powerful reply! ‘Of course I’m a Socialist!’ he ought to have said passionately. ‘How can any decent and reasonably intelligent person be anything else?’ But he lacked the courage to say this in a North Oxford drawing-room, when they hadn’t even started tea.

‘What, you a Socialist?’ said Mr. Bompas. ‘Surely you don’t go to the Labour Club?’

Mr. Cherry, feeling all eyes on him, sat twisting his hands confusedly.

‘I think it’s so nice to have all these clubs,’ said Miss Morrow pleasantly. ‘You must find them a great comfort.’

‘Comfort?’ said Miss Doggett. ‘Whatever should young men of nineteen and twenty be wanting with comfort?’

‘Well, of course they don’t need it in the same way that we do, but surely there is no person alive who doesn’t need it in some way,’ said Miss Morrow, hurrying over the words as if they might give offence.

‘You certainly don’t need it when you’re dead,’ said Mr. Bompas cheerfully.

‘No, I don’t think so,’ said Miss Morrow in a dreamy tone. ‘I think I should certainly need no comfort if I could know that I should be at rest in my marble vault.’

‘I think it is extremely unlikely that you will be buried in a marble vault, Miss Morrow,’ observed Miss Doggett in a dry tone.

At that moment Florence opened the door and announced three more guests. First came two beautiful young men, one dark and the other fair. The dark one was carrying a small cactus in a pot.

‘Oh, Miss Doggett,’ they said, giving the impression of speaking in unison, ‘how wonderful of you to ask us again! It gives us such Stimmung to come here. We’ve brought you a little present.’

‘Oh, Michael and Gabriel, how kind of you!’ Miss Doggett stood with the cactus in her hands, looking for somewhere to put it. ‘Perhaps you would kindly put it on that little table, Mr. Bompas,’ she said, handing it to him.

Mr. Bompas stood up, awkwardly holding the cactus. As far as he could see, the room was full of little tables, and the tables themselves were covered with china ornaments, photographs in silver frames, shells from Polynesia and carved African relics. Not one of them had room for the little cactus. Was he then to be burdened with it all through the afternoon? he thought with rising indignation and a disgusted look at the young men who had brought it. At last, taking care that nobody saw him, he placed it on the floor between himself and Mr. Cherry and sat down again. ‘Mind you don’t tread on it,’ he whispered urgently.

‘You must meet each other,’ said Miss Doggett. ‘Of course Michael and Gabriel are quite at home here,’ she added, smiling. ‘They are in their second year. Whom have you brought with you?’ she asked, noticing for the first time another young man, who was still standing in the doorway.

‘Oh, we didn’t bring him,’ said Michael. ‘He just happened to be coming in through the gate at the same time. But we gave him some words of cheer. Gabriel quoted Wordsworth to him.’

‘Yes, I quoted Wordsworth,’ said Gabriel, in a satisfied tone.

‘Ah, you must be Mr. Wyatt,’ said Miss Doggett triumphantly. ‘Now we can have tea.’

The five young men were now arranged round the room.

Where but in a North Oxford drawing-room would one find such a curiously ill-assorted company? thought Miss Morrow. The only people who seemed really at ease were Michael and Gabriel, but then they were old Etonians, and Miss Morrow was naive enough to imagine that old Etonians were quite at ease anywhere. They sat giggling at some private joke, while the others made an attempt to start a general conversation.

Mr. Wyatt, a dark, serious-looking young man who was reading Theology, asked if anyone had seen the play at the Playhouse that week.

Nobody had.

‘I hope that doesn’t mean that we shall have nothing to talk about,’ said Miss Morrow gravely.

‘Now, Gabriel, you like Russian tea, don’t you?’ said Miss Doggett.

‘Yes, he thinks he is a character out of Chekhov,’ said Michael. ‘He looks perfectly lovely in his Russian shirt. He nearly wore it this afternoon, but we thought it wasn’t quite the thing for North Oxford and we can’t bear to strike a discordant note, can we, Gabriel?’

‘But isn’t there something Chekhovian about North Oxford?’ said Mr. Wyatt unexpectedly. ‘I always feel that there is.’

‘Yes,’ said Miss Morrow, ‘but I don’t think you feel it when you live here. You lose your sense of perspective when you get too close, and the charm goes.’ She said these last words rather hurriedly, hoping that Miss Doggett had not understood their implication.

But Miss Doggett was talking about shirts. ‘I think it is just as well to dress conventionally,’ she said, ‘otherwise I don’t know where we should be. I suppose Mr. Cherry would be appearing in a red shirt.’

‘Oh, really? Do tell us why.’ Michael and Gabriel turned to the unfortunate Mr. Cherry, whose face had turned as red as the shirt he might have worn had he not put on his most conventional blue-and-white-striped one.

‘I suppose Miss Doggett means because I’m a Socialist,’ he said, in a muffled voice.

‘Oh.’ Michael and Gabriel were obviously disappointed at this dull explanation. They were not interested in politics.

‘You have nothing to eat, Mr. Cherry,’ said Miss Morrow, passing him two plates.

He hastily took a chocolate biscuit and then regretted it. When your hands were hot with nervousness, the chocolate came off every time you picked up the biscuit to take a bite.

He ought to have thought of that before, but he had been so grateful to Miss Morrow for offering him something that he had eagerly seized the nearest thing. So often at tea parties you had to wait ages before anyone noticed your empty plate, and when your tea had been finished in nervous little sips there was nothing to do but hope and gaze bravely into space.

Mr. Cherry surreptitiously wiped his chocolaty fingers on his clean white handkerchief. He wasn’t really at ease with people like this, he told himself defensively. He couldn’t be expected to have much in common with this old woman and her companion, those two giggling pansies on the sofa, that hearty Bompas or even with Wyatt, the theological student. He wouldn’t come here again. Next time he would have a previous engagement.

‘Now, Michael, what are you laughing at?’ asked Miss Doggett indulgently.

‘He wants to see the engravings of the Bavarian lakes,’ said Gabriel, ‘but he’s too shy to ask.’

‘I shall be glad to show them to you,’ said Miss Doggett. She turned to the others. ‘Michael and Gabriel are really interested in Art,’ she said impressively. ‘One so seldom finds that nowadays. I don’t mean that hideous stuff you call Art,’ she said suddenly to Mr. Bompas. ‘Not those pictures that might just as well hang upside down.’

Mr. Bompas, whose pictures, being school groups and photographs of actresses, were of the sort that must of necessity hang right way up, had nothing to say to this.

Crampton Hodnet

Crampton Hodnet Quartet in Autumn

Quartet in Autumn No Fond Return of Love

No Fond Return of Love The Sweet Dove Died

The Sweet Dove Died Excellent Women

Excellent Women A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym

A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym Jane and Prudence

Jane and Prudence A Glass of Blessings

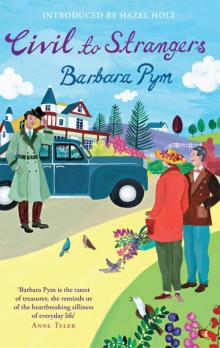

A Glass of Blessings Civil to Strangers and Other Writings

Civil to Strangers and Other Writings An Unsuitable Attachment

An Unsuitable Attachment Less Than Angels

Less Than Angels A Few Green Leaves

A Few Green Leaves Civil to Strangers

Civil to Strangers