- Home

- Barbara Pym

A Few Green Leaves

A Few Green Leaves Read online

'It is funny, it is perceptive, it deals with major concerns — illness, aging, death, the encroachment of big government. But Pym handles them so exquisitely, with such love and humanity, that we chuckle our way through, and only later recognize that she has a message for all of us. ‘

—Miami Herald

‘She surprises comedy and sadness from the most banal and cozy moments without ever managing to be dull.’

—The New York Times Book Review

‘A Few Green Leaves is a beautifully written, very delicate comedy.’

—Times Literary Supplement [London]

‘[It] is like a musical coda. … It will please new readers and old alike… . Her direct, sharply ironic style is almost like speech overheard—the voice of a writer who has come to terms with life and who has no illusions about it. … A few green leaves are all anyone needs.’

—Baltimore Sun

‘Readers … will find it exact, gently amusing and (except for that dubious happy ending) gently heartbreaking.’

—Kirkus Reviews

‘Barbara Pym’s best achievement, though, with A Few Green Leaves is that it reminds us with some ladylike determination that there’ll always be an England of wise spinsters and country retreats, part of the backbone of a bulldog nation known for its inability to admit defeat.’

—Houston Post

A Few Green Leaves

Barbara Pym

Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M4V 3B2 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

Published by Plume, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc. Previously published in an Obelisk/Dutton Paperback edition.

First Plume Printing, November, 1991 10 987654321

Copyright © 1980 by Hilary Walton All rights reserved.

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

Printed in the United States of America

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Publisher’s Note: This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR!

Some Tame Gazelle

Excellent Women

Jane and Prudence

Less than Angels

A Glass of Blessings

No Fond Return of Love

Quartet in Autumn

The Sweet Dove Died

An Unsuitable Attachment

A Very Private Eye:

The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym

(edited by Hazel Holt and Hilary Pym)

Crampton Hodnet

An Academic Question

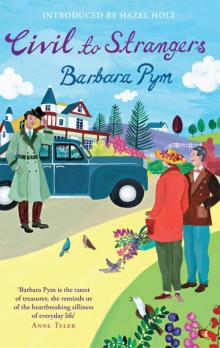

Civil to Strangers and Other Writings,

For my sister Hilary

and for Robert Liddell

this story of an imaginary village

1

On the Sunday after Easter – Low Sunday, Emma believed it was called – the villagers were permitted to walk in the park and woods surrounding the manor. She had not been sure whether to come on the walk or not. It was her first weekend in the village, and she had been planning to observe the inhabitants in the time-honoured manner from behind the shadow of her curtains. But seeing the party assembling outside the pub, wearing tweeds and sensible shoes and some carrying walking-sticks, she had been unable to resist the temptation of joining in.

This annual walk was a right dating from the seventeenth century, Tom Dagnall, the rector, had told her. He was a tall man, austerely good-looking, but his brown eyes lacked the dog-like qualities so often associated with that colour. As a widower he tended not to attach himself to single women, but Emma was the daughter of his old friend Beatrix Howick and rather the type that the women’s magazines used to make a feature of ‘improving’, though this thought had not occurred to Tom. He saw her only as a sensible person in her thirties, dark-haired, thin and possibly capable of talking intelligently about local history, his great interest and passion. Besides, she had recently come to live in her mother’s cottage and he felt he had a certain duty, as rector, to make her welcome.

‘The villagers still have the right to collect firewood –“faggots”, as the ancient edict has it – but they’re less enthusiastic about that now,’ he said.

‘Most of them have central heating anyway or would rather switch on an electric fire when they’re cold,’ said the rector’s sister Daphne. She was fifty-five, some years older than her brother, with a weatherbeaten complexion and white bushy hair. She spoke with feeling, for the rectory was without central heating, but this was not the only reason why her annual Greek holiday was the high spot of her life. She now joined Emma and her brother and began asking Emma whether she had settled down well in the village and whether she was going to like living there; impossible questions to answer or even speculate on, Emma felt.

Behind them walked Martin Shrubsole, a fair, teddy-bear-like young man with a kindly expression, the junior doctor in the practice headed by old Dr Gellibrand – Dr G. as he was called – who was rather past such things as walking in the woods though he would often recommend it to his patients. Martin’s wife Avice walked a few paces in front of him – a characteristic of their married life, some thought. She had been a social worker and was still active in village do-gooding, a tall, handsome young woman, now beating down the encroaching weeds on the footpath with a stout cudgel.

‘This path is supposed to be kept open,' she said fiercely. ‘Soon the nettles will be growing over it.’

‘You can use nettles for all kinds of things,’ said Miss Olive Lee, one of the long-established village residents who remembered the old days at the big house, as she never tired of reminding people, when the de Tankerville family had lived there and Miss Vereker had been governess to the girls. Since then the house had changed hands several times, and as the present owner made little impact on village life it was natural that interest should be concentrated on the past.

‘Nettles? Yes, I’m sure you can,’ said Emma, turning politely to her. She had not yet spoken to Miss Lee, only heard her singing in church, her voice hooting and swooping like an owl or some other nocturnal bird. ‘Would they be something like spinach when cooked? I must try them some time,’ she added doubtfully, wondering how far living in the country need go. ‘Oh, is that the house?’ She stopped walking to stand and gaze at the grey stone mansion now coming into view. Staring up at its blank windows she longed for some intimate detail to manifest itself, even if it were only some small domestic note like a scrap of washing hanging out somewhere. But the windows were as unwelcoming as closed eyes.

‘Sir Miles is not in residence,’ Tom explained. ‘He usually avoids the weekend of the annual walk. In any case, he’s more interested in his shooting.’

‘He avoids us?’ Emma asked, puzzled.

‘Well, not us specifically, but I expect there’ll be a crowd of villagers – they’ll be coming along too.’

At that moment a figure did appear on the terrace, but it was only Mr Swaine, the agent, l

ooking quite genial when he identified the approaching party, such eminently respectable people sponsored by the rector and one of the doctors, not at all the sort to come farther than they were permitted or to take any kind of liberty.

‘A nice day for the walk,’ Tom called out.

‘That’s what comes of having a late Easter,’ said the agent, as if giving Tom the credit for it, perhaps even thinking that it was in his power to fix the date of the festival.

‘Your daffodils are lovely this year,’ said Miss Lee, giving the agent credit for Nature.

‘Yes, we do rather pride ourselves on those,’ he agreed.

Emma glanced at the flowers in the distance. She was becoming rather tired of daffodils. Their Wordsworthian exuberance had been overdone, she felt, crammed into cottage gardens and now such poetic drifts of them in the park and woods. She would have liked to have seen the woods bare in winter, the stark outlines of noble trees – but the rector’s sister had broken in on her thoughts.

‘One goes on living in the hope of seeing another spring,’ Daphne said with a rush of emotion. ‘And isn’t that a patch of violets?’ She pointed to a twist of purple on the ground, no rare spring flower or even the humblest violet but the discarded wrapping of a chocolate bar, as Tom was quick to point out.

‘Oh, but soon there’ll be bluebells in these woods – another reason for surviving the winter,’ she went on. The braying of a donkey at dawn that morning had taken her back to Delphi and the patter of delicate hooves on stone, and she walked on dreaming of the Meteora, the Peloponnese and remote Greek islands as yet unidentified.

At her enthusiastic outburst young Dr Shrubsole moved away from her, hoping that she had not noticed his withdrawal. Although he was a kind man and keenly interested in the elderly and those in late middle age, his interest was detached and clinical. He enjoyed taking blood pressures – even felt an urge to pursue the group of elderly ladies round the rector with his sphygmometer –but was disinclined to enter into other aspects of their lives. He felt that the drugs prescribed to control high blood pressure should also damp down emotional excesses and those fires of youth that could still – regrettably – burn in the dried-up hearts of those approaching old age. Daphne’s outburst about living to see another spring had disturbed him and had the effect of making him join his wife in systematically beating down the undergrowth with his stick, as if violent action could somehow keep Daphne under control.

‘This is supposed to be a public footpath,’ Avice repeated. ‘And what’s that untidy heap of stones?’

‘It might be the site of the D.M.V. – deserted medieval village,’ Tom explained. ‘It’s somewhere here, as far as we know.’

Emma reflected on the cosiness of the term D.M.V., which reminded her of a meat substitute she had once bought at the supermarket when she had been trying to economise, T.V.P. was it? She smiled but did not reveal her frivolous thought.

‘And all this dog’s mercury,’ said Miss Lee, ‘surely that ought to be controlled?’

‘Yes, I’m sorry about that,’ said Tom, as if he could somehow have prevented its growth, ‘but of course it is a sign of ancient habitation, dog’s mercury.’

The party digested this information in silence. They had now moved some distance away from the house and were walking past what looked like a ruined cottage in the woods. Yet, apart from its somewhat overgrown surroundings, it did seem as if it could be iived in, Emma felt. There was a romantic air about it which had been lacking in the house. She began to speculate on its possible history. ‘Perhaps some of these people would know,’ she said innocently, as the sound of a transistor radio heralded the approach of a party of villagers.

Tom laughed. ‘I doubt it,’ he said, but he felt glad, rejoiced almost, that they were exercising their right to enter the park and woods very much as they must have done in the seventeenth century, except for the mindless mumbling of the radio which its owner had not troubled to turn down. He said as much to Emma and she agreed that it was good to see the old right still maintained, though she reflected that the radio was not the only difference between now and three hundred years ago. It was noticeable that all the younger people were wearing jeans, but that the older members of the villagers’ party were wearing newer, smarter and more brightly coloured clothes than the rector and his group.

Greetings were exchanged on an equal level. Tom made no attempt to enquire after relatives or children and grandchildren or even livestock, as the Lord of the Manor or his own predecessors might have done. He had noted among the villagers Mrs Dyer, the woman who came to clean at the rectory, and her presence inhibited any attempt at that kind of conversation. He knew that very few of them would be at Evensong. Of his own party this afternoon he could rely only on his sister, Miss Lee – and possibly Miss Grundy (‘Flavia’), a woman somewhat younger than Miss Lee, but still very much of uncertain age, with whom she shared a cottage, might also be there. But Tom suspected that Miss Grundy’s preference was for Solemn Evensong and Benediction rather than the simpler village service which was all that he could offer. The young doctor and his wife seldom came to church and Emma, though she had been once out of curiosity, was an unknown quantity. He knew from her mother that she was some kind of scientist, and that she had come to the village to write up the results of a piece of research on something or other. It occurred to him that even if she didn’t come to Evensong, she might be helpful in other ways. She might be a good typist, though he could hardly ask her to do such menial work, or even be expert at deciphering Elizabethan handwriting, a skill none of his willing lady helpers possessed.

2

After the walk Emma went back to Robin Cottage, so named by a former owner because the bird had once appeared when he was digging his vegetable patch and perched on the spade. The cottage now belonged to Emma’s mother Beatrix, who was a tutor in English Literature at a women’s college, specialising in the eighteenth-and nineteenth-century novel. This may have accounted for Emma’s christian name, for it had seemed to Beatrix unfair to call her daughter Emily, a name associated with her grandmother’s servants rather than the author of Wuthering Heights, so Emma had been chosen, perhaps with the hope that some of the qualities possessed by the heroine of the novel might be perpetuated. Emma had so far failed to come up to her mother’s expectations but had become – goodness only knew how – an anthropologist. Nor had she married or formed any other kind of attachment. Beatrix would have liked her to marry – it seemed suitable – though she did not herself set all that much store by the status. Her own husband – Emma’s father – had been killed in the war, and having, as it were, fulfilled herself as a woman Beatrix had been able to return to her academic studies with a clear conscience.

Emma, if she thought about her name at all, was reminded not of Jane Austen’s heroine but rather of Thomas Hardy’s first wife – a person with something unsatisfactory about her. Now she made herself a cup of tea, feeling that she might have asked the rector and his sister back to share it with her. But then she realised that she had no cake, only the remains of a rather stale loaf, and anyway he would have Evensong. She knew the times of the services and had been to church once but did not intend to become a regular churchgoer yet. All in good time, when she had had a chance to study the village, to ‘evaluate’ whatever material she was able to collect. For the moment she would go on writing up the notes she had completed before coming to the village – something to do with attitudes towards almost everything you could think of in one of the new towns. Here, in this almost idyllic setting of softly undulating landscape, mysterious woods and ancient stone buildings, she would be able to detach herself from the harsh realities of her field notes and perhaps even find inspiration for a new and different study.

Too soon, for she had done no work, Emma began to think about supper. What did people in the village eat? she wondered. Sunday evening supper would of course be lighter than the normal weekday meal, with husbands coming back from work. The shepherd’s

pie, concocted from the remains of the Sunday joint, would turn up as a kind of moussaka at the rectory, she felt, given Daphne’s passionate interest in Greece. Others would be taking out ready-prepared meals or even joints of meat from their freezers, or would have bought supper dishes at the supermarket with tempting titles and bright attractive pictures on the cover.

Sometimes there might even be fish, for a man called round occasionally with fresh fish in the back of his van, suggesting a nobler time when fish had been eaten on Fridays by at least a respectable number of people in the larger houses. Had there even once been Roman Catholics in the village? Then there were people living alone, like herself, who would make do with a bit of cheese or open a small tin of something.

It would have to be an omelette, the kind of thing that every woman is supposed to be able to turn her hand to, but something was wrong with Emma’s omelette this evening – the eggs not enough beaten, the tablespoon of water omitted, something not quite as it should be. But she was hungry and did not care enough to analyse what her mistake could have been. It was better not to be too fussy, especially if one lived alone, not like Adam Prince opposite, who travelled round doing his job as an ‘inspector’ for a gourmet food magazine, spending his days eating – tasting, sampling, criticising (especially criticising), weighing in the balance and all too often finding wanting. Emma’s mother had told her that before his present job he had been an Anglican priest who had ‘gone over to Rome’, but she had not enlarged on this bald statement. He was away now, for Emma had noticed meticulous instructions to the milkman to that effect on the complicated plastic contraption outside his door which told exactly how much milk he did or did not want.

Crampton Hodnet

Crampton Hodnet Quartet in Autumn

Quartet in Autumn No Fond Return of Love

No Fond Return of Love The Sweet Dove Died

The Sweet Dove Died Excellent Women

Excellent Women A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym

A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym Jane and Prudence

Jane and Prudence A Glass of Blessings

A Glass of Blessings Civil to Strangers and Other Writings

Civil to Strangers and Other Writings An Unsuitable Attachment

An Unsuitable Attachment Less Than Angels

Less Than Angels A Few Green Leaves

A Few Green Leaves Civil to Strangers

Civil to Strangers