- Home

- Barbara Pym

The Sweet Dove Died Page 4

The Sweet Dove Died Read online

Page 4

‘Desirable Victoriana—not quite me, but still.’

‘Then there’s a mirror with cupids, fruitwood — that’s rather pretty.’ Leonora had always admired it excessively; perhaps it was unwise of him to have mentioned it. ‘I ought to be going,’ he said.

‘I suppose you’ve got a date this evening.’

‘Yes, I have, in a way.’ Dining with Leonora didn’t exactly count as a ‘date’.

‘I could make you a cup of tea.’

‘That would be nice, but hadn’t you better …?’ He looked at her bare shoulders doubtfully. ‘Somebody might call.’

‘They might, too. This village believes in dropping in. I suppose this sheet would do as a sarong but I don’t seem able to arrange it properly.’ Phoebe struggled back into her jeans and put on a crumpled white cotton shirt. ‘Is that better?’ He must still have looked doubtful for she said rather crossly, ‘Oh, well, it’ll do to make tea in,’ and crept barefoot down the stairs.

James waited uneasily in the sitting-room. He began to feel that he had behaved most unwisely. Why had he let himself get entangled with Phoebe like this? Yet what was ‘entangled’? Surely he need not feel any obligation towards a girl who had thrown herself at him?

‘Will you come again?’ she asked frankly. ‘Or perhaps you’ll invite me to your flat sometime?’

‘Yes, I’ll do that — we could have dinner. I’ll give you a ring.’

‘Then I can see the furniture!’ She laughed. ‘How practical I’m being. Shall I come out to the car with you?’

‘Not with your bare feet.’

‘All right, I’ll just kiss you goodbye here. Oh James, what did we do?’

What indeed? he wondered, as he drove back to London. He hoped there wouldn’t be any traffic jams, for Leonora would expect him to be punctual. She hated him to be late. That was the worst of being attached to an older woman, though ‘worst’ was surely the wrong word to use in connection with anyone as delightful as Leonora.

VI

There was a little park near Leonora’s house and it was here that she had asked James to meet her, so that they could have a walk before dinner. He had agreed rather unwillingly and now he felt decidedly tired after his exertions in the country and would have preferred to sink into a chair with a drink at his elbow rather than traipse round the depressing park with its formal flowerbeds and evil-faced little statue — a sort of debased Peter Pan—at one end and the dusty grass and trees at the other. Wasn’t it a slight affectation on Leonora’s part to find it so ‘agreeable’ and the statue so ‘appealing’?

‘ There you are, darling—and just a little late. Did the traffic hold you up or something? One knows how it can at this time of day.’

James bent his head to kiss her. A faint breath of heliotrope—Leonora’s favourite L’Heure bleu—came to meet him. He wondered if she noticed anything different in his manner; a hint of Phoebe’s scent lingering about him might arouse her suspicions. Then he realised that Phoebe didn’t use scent and he had changed and had a bath; his imaginings were old-fashioned and ridiculous like a novel of the thirties.

‘Well, there was traffic, of course,’ he began, feeling guilty and trying to remember what he had done after leaving Phoebe. He had gone straight home and prepared himself to meet Leonora, he thought, his sense of virtue tinged with cynicism. There hadn’t even been time for a drink. ‘You look wonderful in that colour,* he said, moving away from her to admire the amethyst-coloured dress she was wearing. ‘It’s autumnal, somehow.’

‘You mean that I look old? That I’m in the autumn of life?’

‘You know I didn’t mean that! And anyway autumn is a much pleasanter season than spring or summer, much more agreeable.’ He smiled as he used one of her favourite words.

Leonora looked up at him affectionately. ‘Did you enjoy going round the country antique shops today?’ she asked.

‘Yes, quite. I suppose I might have bought something, but I just priced the things, and then I found myself driving through a village where there was a jumble sale going on, so I went in there.’James stopped, afraid that he might go too far.

‘And did you find some rare treasure?’

‘Only a little china castle and that was cracked.’ A bit like Phoebe, perhaps. What was Leonora like? A piece of Meissen without flaw? It would be an amusing game to liken one’s friends and acquaintances to antiques.

‘Humphrey won’t be very thrilled with that,’ said Leonora. ‘I’m sure you’re not supposed to go to jumble sales, my love.’

‘I know—I got drawn into this one, somehow. But you can bet that if Humphrey had gone he’d have found something special. He always has better luck than I do,’ said James disconsolately.

‘You can hardly say that—after all, you both found me, didn’t you?’

‘Yes, of course, at Sotheby’s that day. How was your expedition with Humphrey this afternoon?’

‘Lovely! We went to Virginia Water. All those trees and distant ruins, so much me.’

‘I wish we were walking in some beautiful garden now,’ James sighed.

‘Some giardino or jardin— perhaps the Estufa Fria in Lisbon.’ Leonora smiled. ‘That funny old Professor — did I ever tell you?’

Leonora had had romantic experiences in practically all the famous gardens of Europe, beginning with the Grosser Garten in Dresden where, as a schoolgirl before the war, she had been picked up by a White Russian prince. And yet nothing had come of all these pickings-up; she had remained unmarried, one could almost say untouched. It was all a very far cry from the dusty little park where she and James now walked.

‘And then there was Isola Bella—that tree with the great leaves—Elefantenohren . . .’ She broke into laughter at some memory James could not share.

He glanced up at the undistinguished trees around them. ‘Haven’t we had ehough of a walk now? It’s getting dark—somebody’s blowing a whistle and it looks as if that man is about to lock the gates. We don’t want to be locked in, do we.’

‘Don’t worry, he’s a sweet little man and he’s often opened the gate for me. There’s no need to hurry.’

Nevertheless James felt that the man was not very pleased at having to unlock the gate for them. Obviously it was only with Leonora that he was ‘sweet’.

‘How charming your house looks,’ said James, as they approached it.

‘Yes, doesn’t it — and do you know, I think I’m going to be able to buy it soon, so it will really be mine and I can do what I like with it.’

‘Will you have to buy Miss Foxe with it?’

‘Yes, but one hopes to be able to get rid of her pretty soon.’

Leonora spoke so forcibly that James gave her a startled look.

‘Here she is,’ she whispered harshly, as they entered the front door.

James saw a white-haired, fragile-looking woman of about seventy, wearing a grey dress and a string of perhaps good pearls, who appeared to be struggling to lift a paraffin can up the stairs.

James ran forward. ‘Do let me carry that for you,’ he said.

‘Oh, how kind! It really is heavier than I thought.’ She had a fluty, well-bred voice.

‘Much too heavy for you to carry,’ said James gallantly. ‘She shouldn’t have to do that,’ he said afterwards to Leonora.

‘Darling, you’re so thoughtful and one loves you for it,’ said Leonora in her coolest tone, ‘but what a fuss. It was only a two-gallon can and it couldn’t have been so very heavy. And anyway what on earth does she want with paraffin at this time of year?’

‘Well, I suppose it’s cheaper than electricity or gas and the evenings are still rather chilly,’ he said.

‘Oh, very chilly,’ Leonora mocked. ‘One feels that using paraffin at all is somehow degrading—the sort of thing black people do, upsetting oil heaters and setting the place on fire. Really, it’s rather frightening to think of her up there—that’s why one will simply have to get rid of her when her lease runs out.’

James made a faint murmur of protest. One day Leonora would be old herself, but obviously it wouldn’t be the same.

‘One has to be tough with old people,’ Leonora went on, ‘it’s the only way—otherwise they encroach.’

‘Don’t let’s talk about her,’ said James uncomfortably. ‘I feel I’ve earned a drink.’

A few minutes later he sat relaxed with a gin and tonic, enjoying Leonora’s conversation flung at him from the kitchen where she was putting the finishing touches to the meal. They had a cosy arrangement of telling each other of the day’s happenings, either by meeting or by telephone, but James could not be as frank as usual about his day and was content to listen to Leonora describing in detail her expedition with Humphrey to Virginia Water. He really did not want to say much more about the village jumble sale and hoped that one or two amusing observations would be enough and that he could be left to enjoy his drink and gaze around him at Leonora’s pretty room.

It was a pleasing setting for her, with its pale green walls and trailing plants —for naturally Leonora was ‘good’ with house plants. Some of the pieces of furniture had come from Humphrey, but James himself had provided a few trivia or ‘love tokens’, as she called them, and he supposed that was what they were even though it was she who had labelled them thus. Her love of small Victorian objects made it easy for James to find suitable trifles to express his devotion.

‘Asparagus!’ he exclaimed, as she came out of the kitchen with a dish. ‘The first this year.’

‘Then you must have a wish.’

James was embarrassed, as one usually is when commanded to make a wish.

‘A secret wish of course, darling,’ Leonora reassured him.

I have no secrets from you, was what he wanted to say but the glib words would not come. Whatever would a meal with Phoebe be like? he wondered, when Leonora brought in the next course which was chicken with tarragon.

‘You’re looking particularly handsome tonight,’ she teased. ‘I wonder how many people have fallen in love With you today?’

One at least, he thought uncomfortably. To his chagrin he felt himself blushing, and yet by now he was quite accustomed to this particular kind of teasing from Leonora. Sometimes it seemed almost as if she had created him herself—the beautiful young man with whom people were always falling in love and who yet remained inexplicably and deeply devoted to her, a woman so much older than he was. James had been content to play this part and of course there was no doubt of his devotion to Leonora. But now there was Phoebe—or was there? It was certainly not part of Leonora’s plans for him, if she had any, that he should become devoted to a younger woman. But somehow the word ‘devotion’ didn’t seem applicable to what had taken place in Phoebe’s cottage this afternoon.

James was relieved when Leonora came back from the kitchen with a chocolate mousse, a favourite dish she often made for him. No need to brood over Phoebe now. Afterwards there would be coffee and perhaps music or just talking. Sometimes James would tell her about his childhood in America or read poetry to her while she toyed with a piece of tapestry work, her beautiful dark blue eyes looking up at him over the tops of her glasses. The glasses had become a joke between them—’one’s failing sight, so middle-aged’.

Tonight James had with him a copy of Sotheby’s catalogue, describing a forthcoming sale of furniture which he thought would interest her. Reading from sale catalogues was another of their favourite diversions and there was nothing Leonora liked better than to hear James’s pleasing voice reading out the seductive descriptions which brought the beautiful pieces before her eyes—narrow crossbandings of tulip wood, palm tree motifs and eagles cresting … the poetry of the phrases flowed over her in a delightful confusion so that she hardly knew what was being described, only that it was something exquisitely desirable, and that this was being another of their ‘lovely evenings’.

VII

Leonora had little use for the ‘cosiness’ of women friends, but regarded them rather as a foil for herself, particularly if, as usually happened, they were less attractive and elegant than she was. When Meg rang her to arrange a meeting for lunch, her first instinct was to make an excuse, but since she had become friendly with James she had felt increasingly curious about Meg’s relationship with Colin. Then, too, she had not seen her since the evening when Meg had called on her in such distress. Presumably Colin had now ‘come back’, or however one would express it, and certainly Meg sounded happy, almost exuberant, when she asked Leonora to meet her at a snack bar in Knightsbridge at a quarter to one.

Leonora was her usual few minutes late, though not as late as she would have been if meeting a man. Meg was one of those women who are always too early and can be seen waiting outside Swan and Edgar’s, with anxious peering faces ready to break into smiles when the person awaited turns up.

‘There you are!’ she exclaimed, as Leonora strolled to meet her.

Leonora greeted her but did not apologise. Meg was looking tidier than when they had last met. She was wearing a light spring coat in a shade of green that did not suit her particularly well, but her hair had been newly done and—or so it seemed to Leonora—the grey streaks disguised with a brown rinse.

‘You’ll never guess why I suggested we should meet here,’ said Meg.

‘Well, it’s convenient for Harrods and one often wants to go there.’

Meg looked blank. Obviously Harrods meant nothing to her. ‘It’s Colin,’ she explained. ‘He’s got a job here.’

Leonora expressed surprise; perhaps congratulation also was called for, but she would keep that in reserve until she knew more of the circumstances.

‘We must go downstairs,’ said Meg, ‘where they have the salads. Do you mind? You take a tray and choose what you want from the counter.’

Leonora followed her into a dimly lit basement whose orange and purple walls were hung with abstract paintings. Behind the counter she was just able to discern two figures—a long-haired girl wearing round tinted glasses—however did she manage to see anything?—and Colin. Both were serving out raw salads from a number of dishes.

‘Hullo, Leonora,’ said Colin smoothly. ‘What are you going to have?’

‘I don’t know—what is there? Some pate, perhaps, and what do you think would go best with it? You must help me choose.’ Leonora was at her most appealing, but in the dim light it was hardly possible to see what the dishes contained. Colin was also at his most appealing and Meg beamed proudly at the sight of him, so efficient and charming in a pink flowered shirt.

‘A friend of Harold’s got him the job,’ she explained, when they had settled themselves at a cramped little table in a corner. ‘He seems to be doing very well and he likes it, which is so important.’

‘Hardly the kind of thing to make a career of, though,’ said Leonora, looking around her. This was most definitely not her kind of place, she decided —everyone so young, the girls appallingly badly dressed by her standards, all talking too loudly in order to make themselves heard above the background of pop music. ‘Surely you don’t come here often?’ she asked.

‘Well, it’s a bit far from the office,’ Meg admitted, ‘so I don’t come every day. But when Colin first took this job I think it gave him confidence to know that I was here. And of course it’s so good for one, all this’—she indicated the coarsely shredded cabbage on her plate.

Leonora felt she would have said the same had it been grass they were eating. ‘I gather then that things are better,’ she said delicately.

‘Oh, much better. Just a sort of misunderstanding really, that’s all it was. You have to let people be free,’ said Meg, in the brave manner in which she had spoken of Colin’s ‘lovers.’ ‘In that way they come closer to you.’

Leonora smiled but said nothing.

‘We went out to the theatre last night,’ Meg went on. ‘Colin and I and Harold and his mother.’

‘That must have been a strange party.’

‘I suppose it was,

when you come to think of it. And the show wasn’t really what I’d have chosen myself,’ she named a musical which had been running for over a year, ‘but it was an interesting experience.’

‘Does one really want to have “interesting experiences” at our age?’ Leonora asked. ‘I’m not sure that I do.’

‘Oh, you’re different. You must have had so many already, living abroad and always being so much admired,’ said Meg generously.

Leonora smiled again, more warmly this time, though she was less pleased when Meg went on to say that she didn’t think of Leonora as the sort of person who had ‘experiences’ now.

‘How do you think of me, then?’ Leonora asked.

‘Just living in your perfect house, leading a gracious and elegant life,’ said Meg. ‘It’s hard to explain,’ she added, seeing a shadow of displeasure cross Leonora’s face.

‘You make me sound hardly human, like a kind of fossil,’ Leonora protested.

‘I didn’t mean that—it’s just that I never think of you as being ruffled or upset by anything. Not like me—that awful night when I burst in on you, whatever must you have thought!’

‘People react in different ways. One may not show emotion, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that one doesn’t feel it.’

‘I’ll get us some coffee.’

While Meg was away Leonora thought over what she had said. She was not sure that she liked the picture of herself it suggested. Of course one wasn’t like that at all, cold and fossilised. It was only that all one’s relationships had to be perfect of their kind. One would never have put up with anything as unsatisfactory as Colin’s behaviour, for instance.

‘Not the best coffee in London,’ said Meg apologetically, returning with two cups. ‘I thought it safer to get it black. Look how busy they are now—Colin says it’s murder between one and two.’

‘What a good thing we came early, then. This has certainly been an “interesting experience” for me.’ Leonora touched her immaculately tidy hair and drew on her gloves.

Crampton Hodnet

Crampton Hodnet Quartet in Autumn

Quartet in Autumn No Fond Return of Love

No Fond Return of Love The Sweet Dove Died

The Sweet Dove Died Excellent Women

Excellent Women A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym

A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym Jane and Prudence

Jane and Prudence A Glass of Blessings

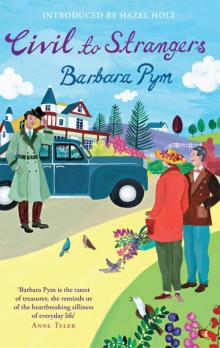

A Glass of Blessings Civil to Strangers and Other Writings

Civil to Strangers and Other Writings An Unsuitable Attachment

An Unsuitable Attachment Less Than Angels

Less Than Angels A Few Green Leaves

A Few Green Leaves Civil to Strangers

Civil to Strangers