- Home

- Barbara Pym

No Fond Return of Love Page 7

No Fond Return of Love Read online

Page 7

‘I must be going,’ said Laurel, wondering if she had frightened him with her brittle, party manner. ‘Oh, and the plant — how much is it?’

‘Three and six,’ he said.

Laurel found a half-crown and two sixpences in her purse; she could hardly have borne to have received change from him.

‘Goodbye,’ she said, ‘and thank you again.’

Paul would have liked to say something more, to ask her to go out with him one evening, but he was too shy to think of anything quickly enough.

A pity he’s so dumb, Laurel thought, hurrying out into the dusk, but there would surely be other meetings. The encounter, as was only to be expected when it had taken place in anticipation so many times, had been disappointing. Paul seemed younger and more callow than she had remembered, though his brown eyes were even more beautiful. Perhaps, really, she liked older men better; even the slightly ridiculous gallantry of Senhor MacBride-Pereira, whom she met in the road, was not unpleasing to her.

‘A young English girl with a pot plant — what could be more charming …’

It was difficult to know how to answer this. Perhaps a Brazilian girl would not be seen carrying a pot plant and the sight was therefore unusual?

‘I’ve bought it for my room,” she said.

‘Ah, your “bed-sitter”. He brought out the word triumphantly, for he prided himself on his command of English slang.

Laurel watched him walk slowly away towards the pillar-box, turning out his feet in their orange suede shoes.

When she reached her aunt’s house, she saw a taxi outside the gate. The driver, grumbling under his breath, was unloading suitcases and carrying them into the house. In the hall she found her aunt and a tall, untidy-looking woman in a rather dirty red coat, anxiously counting out money. Then she remembered with a slight sinking feeling that this was the evening when Miss Dace — Viola — was coming to stay. Dulcie had warned her about it at breakfast.

Repressed spinster, thought Laurel dispassionately, for Dulcie had said that she might be ‘in rather a nervous state’. Life had, apparently, been a bit difficult. Well, it usually was, thought Laurel with all the easy scorn of her eighteen years. Life might improve if Miss Dace — could one possibly call her Viola? — were to send that coat to the cleaner and get herself a new hair style.

‘This is my niece Laurel,’ said Dulcie rather nervously. She had put a macaroni cheese in the oven and was now worrying lest it should not be enough. ‘I expect you’re in the middle of cooking dinner,’ Viola had said, which made Dulcie wonder whether she had not better open a tin of some kind of meat and have the macaroni cheese as a first course. Viola had always seemed to eat so little, and was it not, perhaps, better to begin as one meant to go on, with the bigger meal in the middle of the day and a rather small supper? Surely she would not expect meat twice a day?

Viola also had her thoughts. It had seemed such a very long way in the taxi, as she watched the fare mounting up on the clock and familiar landmarks were left behind. Olympia had seemed the last bulwark of civilization. And then, when they came to the suburban roads, with people doing things in gardens, she had wanted to tap on the glass and tell the driver to turn back. Now, standing in the hall, she saw that the house was quite spacious. There was a glimpse of a pleasant garden through french windows — just like a scene in a play. Through another open door she could see a table laid for a meal — and there were several decanters on the Edwardian oak sideboard, one of which had some brownish-looking liquid in the bottom. Could it be whisky or sherry or brandy, perhaps, kept for ‘medicinal’ purposes only?

‘You’ll want to see your room,’ said Dulcie, fussing rather. ‘I’m afraid it’s got some old pictures in it — I mean just old, not in the sense of Old Masters. My mother was fond of them — they had belonged to her mother — so you see …’

‘Yes, the taste of another age,’ said Viola in a detached tone, examining the pictures. ‘How very prosperous “Prosperity” looks, with that elaborate coiffure, lace at the throat, and all those pearls. And beside her, on that well-polished mahogany table, a dish — or perhaps an epergne — filled with hot-house grapes and peaches.’

‘Yes, but she has a nice expression,’ said Dulcie. ‘Like the wife of a Conservative Member of Parliament about to open a bazaar, don’t you think?’

‘“Adversity” seems more modern,’ Viola continued. ‘That lank hair and waiflike expression — one sees so many typists and girls in coffee bars looking like that.’

‘This is your bed, of course,’ said Dulcie, indicating the divan with its striped folk-weave cover. ‘It’s rather narrow, but quite comfortable, I think.’

Viola examined it, testing the mattress with her hand, as if Dulcie were an ordinary landlady and she were deciding whether to take the room or not. ‘I’m sure it will be quite comfortable,’ she said.

‘The bathroom is at the end of the passage,’ said Dulcie, ‘and supper will be ready whenever you are. There’s nothing to spoil.’

Then it couldn’t be anything exquisite like a lobster souffle, Viola thought. She would smoke a cigarette while unpacking, and take her time. After a while she ventured out to the bathroom. It was an old-fashioned comfortable room with a faded rose-patterned carpet on the floor and the bath encased in mahogany. A shelf on the wall held a selection of books, their covers now faded and buckled by steam. Viola noticed The Brothers Karamazov, Poems of Gray and Collins, Enquire Within, The Angel in the House, and a few old Boots Library books, A Voice Through a Cloud, Some Tame Gazelle, and The Boys from Sharon. By the bath there was a tin of Gumption and a rag. Does she expect me to clean the bath.’ thought Viola with a sudden uprising of indignation. Of course one gave it a token swill around after use, leaving it perhaps not exactly as one would wish to find it, but Gumption and all that was hardly what she had expected. She went down to supper still feeling slightly indignant, as if she had really been giving the bath a good clean instead of only imagining herself doing it.

‘There is some sherry here,’ said Dulcie in a surprised tone, going to the sideboard and lifting up the decanter Viola had seen through the open door. ‘Would you like some?’

‘Thank you, that would be nice …”

‘Macaroni cheese is the first course. Then there will be cold meat and salad,’ said Dulcie rather firmly. ‘Is that sherry all right?’

‘Actually it seems to be whisky, but that’s even better.’

‘How stupid of me! I don’t drink much myself, and now that I come to think of it my father did keep his whisky in that decanter. Wouldn’t you like some water or soda with it?’

Sometimes neat whisky is the only drink, thought Viola, declin-ing Dulcie’s offer and wondering if there were to be many such meals, with the two of them making polite conversation and the silent niece watching them with the critical eyes of youth.

Let them get on with it, thought Laurel. She would be off to her bed-sitting-room in Quince Square as soon as there was a vacancy in the house where Marian lived. She tried to cheer herself up by thinking of Paul, but all she could remember were his cold-looking hands and the wreaths of wax flowers not favoured by the better-class Kensington residents.

Fancy that whisky being here all this time! thought Dulcie.

Nobody had touched it since Father’s death three years ago. A house where there was drink that was not drunk — she had not imagined that her house would be such a one. She would go to the wine merchant tomorrow and order something suitable. But was this ‘beginning as she meant to go on! Wouldn’t it better to let Viola bring in her own secret bottles?

The meal finished. ‘Shall we wash up before we have coffee?’ Dulcie asked. ‘I always think it’s nice to get the things out of the way.’

‘Just as you like,’ said Viola, who had not imagined herself washing up. Her inclination would have been to leave everything till the morning.

Laurel seemed to have disappeared to her room and soon afterwards the house was filled with s

ound — voices singing, if it could be called that, about somebody or something called a Bird-Dog — at least, that was how Dulcie in her confusion heard it, though perhaps it could hardly have been that. What were they going to do all the time, she and Viola, she wondered, as Viola silently dried the silver. Was the companionship of this rather odd woman what she really wanted? Supposing she did not get on with her after all?

These thoughts, and others like them, went through Dulcie’s head as she stood bowed over the sink, but all she said was, ‘What about breakfast? What time would you like it?’

‘Oh, I never eat it, thank you. If I could just make tea in my room — I see there’s a gas-ring.’

‘Yes, of course,’ said Dulcie, relieved. ‘I’ll give you the things.’

‘I shall be rather busy,’ said Viola casually, ‘so you may not see very much of me.’

‘You have some special job, then?’

“Yes. Aylwin has asked me to do the index for his new book.’

‘Oh?’ Dulcie was conscious of a ridiculous pang of jealousy. It was really too silly.

‘Yes — it’s really best that I should do it because I did help him a lot with the book,’ said Viola, rather smugly.

‘I suppose he’s paying you for it?’ Dulcie asked, her brusque tone concealing the twinge of unworthy envy she felt at the idea of it.

‘Well, no …’ Viola hesitated. She did not want to admit to Dulcie that she had offered to do Aylwin’s index, unfairly waylaying him on the steps of the British Museum so that he could hardly have refused.

‘Oh, then you’ll get some kind of acknowledgment in the foreword,’ said Dulcie, trying to make light of it. ‘Something about your having undertaken the arduous or thankless — though I hope it won’t be that — task of compiling the index. But why didn’t you tell me before?’

‘I didn’t know till yesterday.’

‘How — splendid!’ Dulcie emptied the washing-up bowl with a violent movement. ‘And are you still — er — fond of him?’

Viola did not answer.

‘Well, I hope you are,’ Dulcie went on. ‘I can imagine few tasks more distasteful than making an index for someone for whom one no longer cares. Or for whom one has ceased to care,’ she emended, as if perfecting her little aphorism.

‘There are some people one could never cease to care for,’ said Viola, ‘and I suppose Aylwin is one of those.’

‘Obviously every man must be that to some woman,’ said Dulcie, ‘even the most unworthy man.’ She had been thinking of Maurice, but surely she had ceased to ‘care’ for him? ‘Of course,’ she went on, ‘those are the people from whom one asks no return of love, if you see what I mean. Just to be allowed to love them is enough.’

‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ said Laurel stiffly, coming into the kitchen with a little saucepan. ‘I thought I might make some coffee.’

‘There’s plenty of milk in the larder,’ said Dulcie, reassuming, much to Laurel’s relief, her normal auntlike manner. ‘Take it from the bottle that’s already started. Would you like to have coffee with me this evening?’ she said to Viola. ‘I don’t suppose you’ll want to get started on the index tonight, will you?’

It was nice to think that Laurel was really using that gas-ring, making herself coffee. Soon the three of them would all be making their little separate drinks.

Chapter Nine

IT WAS November before Dulcie managed to find a convenient afternoon for her expedition to Mrs Williton’s house in Deodar Grove, a sad autumn day with the leaves nearly all fallen from the trees and the sky colourless, with no promise of brightness in it. She wished she had a dog to run ahead of her over the rough grass of the common, and envied two young men with a small mongrel which ran backwards and forwards ecstatically from one to the other. Then she saw that they were not as young as she had at first supposed, and the discovery added to the general melancholy of the scene — those two and their little dog against a hostile world. They talked to each other in low voices and regarded her suspiciously, though she could hardly imagine why. She plodded on in her sensible shoes, glad that she had put on a raincoat, for a few spots were beginning to fall.

On the other side of the common she could now see a row ofhouses. According to the map this should be Deodar Grove. It was possible to see that the houses were quite large and that most of the windows were heavily curtained in various kinds of nylon net. They had small front gardens planted with shrubs and a few decaying chrysanthemums. As she came nearer Dulcie saw that one house had a ‘To be Sold’ notice attached to the front wall. Fortunately it was next door to Mrs Williton’s house, so that Dulcie felt justified in stopping and staring rather more intently than she could otherwise have done. The house for sale had nothing remarkable about it except a small stone squirrel, perched on a rockery in the front garden, a rather worn-looking little creature with its paws tucked up appealingly under its chin. But Dulcie was interested to notice that a good deal of bustle was going on next door — women, carrying shopping bags and parcels, were going up to the front door and walking in.

‘Excuse me…’

Dulcie turned to see a tall dark woman with a long pale face at her side.

‘That is Mrs Williton’s house, I suppose, where everyone has been going in? I can’t remember the number — my sister knew, but she and my niece have gone shopping this afternoon. Deirdre — my niece, that is, is expecting a baby.’

‘Oh,’ said Dulcie, rather taken aback, ‘how nice for her!’

‘And if it’s a boy,’ went on the woman in a fond tone, ‘he’s going to be an anthropologist like his daddy.’

‘Goodness!’ said Dulcie.

‘That’s just Digby’s little joke, of course. He’s my nephew by marriage of course — nephew-in-law, I suppose you’d say. Should we go in, do you think? I can’t remember what time it said on the card — it must have got thrown away.’

‘Yes, cards do tend to get thrown away,’ said Dulcie, confused and a little excited, for so many women had been going into the house that it occurred to her that there was no reason why she should not join them.

‘Let’s venture then, shall we?’ said the woman, sweeping Dulcie along with her. ‘Mabel thought it would be in the drawing-room at the back — it’s quite a big room.’

What would be in the drawing-room at the back? Dulcie wondered, not liking to ask and hoping that it was not essential that she should know.

‘As a matter of fact,’ said her companion, ‘I have brought a few little things with me — some chutney and lemon curd, home-made of course — though it isn’t exactly that kind of a sale. But every little helps, doesn’t it, and it’s such a good cause. Oh, look, it is half past three, not three o’clock, so we’re not late after all.’

Dulcie looked and saw pinned to the front door a large hand-lettered poster. It said JUMBLE SALE — IN AID OF THE ORGAN FUND’. What a piece of luck, she thought, wondering for one wild moment if she could run back and snatch the stone squirrel from the garden of the empty house so that she too might have something to bring. But if she had brought nothing, she could perhaps buy.

‘Ah, Miss Wellcome,’ a little round woman had greeted Dulcie’s companion, ‘welcome, if I may say so!’

‘How good of you to have the sale in your drawing-room, Mrs Williton,’ said Miss Wellcome, most fortunately identifying the woman Dulcie had come to see.

‘Well, I thought it would be more convenient here,’ said Mrs Williton, ‘and after all it isn’t as if it’s an ordinary jumble sale — just among ourselves really, isn’t it. How good of you to come,’ she said turning to Dulcie. ‘Are you new in the parish?’

‘No, I mean, I was just passing and thought I might come in. I can’t resist a sale of any kind,’ said Dulcie. ‘And it did seem to be such a good cause, the organ,’ she murmured.

‘Yes, we all feel that Mr Lewis is worthy of a better instrument. You probably weren’t in church last Sunday evening, so you didn’t hear the little speech he m

ade, so charming…. And now I must get back to my stall — I’ve got my girlie helping me.’ She turned to Miss Wellcome and said in a low tone, ‘I expect Mrs Swan told you about that. Well, there it is — I always knew something like this would happen. I was afraid of it from the very first,’ she added on a triumphant note.

Dulcie turned away, overwhelmed by the richness of the occasion. It was really more than she could possibly have hoped for. ‘My girlie’ — obviously Aylwin Forbes’s wife — was, surely, the fair-haired young woman wearing a mauve twin-set, standing behind one of the trestle tables which had been arranged as stalls. Yet, thought Dulcie, going over to the stall, was she really quite young enough for that fluffy shoulder-length hair style? A closer inspection revealed that she was nearer thirty-five than twenty-five.

‘How charming,’ said Dulcie, boldly picking up a little pottery donkey drawing a cart. ‘I can see that this is no ordinary jumble sale,’ she added falsely, hoping that Mrs Aylwin Forbes would speak.

‘No — people have really been very kind sending such treasures,’ said Marjorie Forbes. ‘It is sweet, isn’t it.’

Impossible to tell whether she spoke ironically or not, Dulcie decided. Yet surely she could not have thought the object in question anything but tasteless and hideous?

‘Why, it is a calendar!’ said Dulcie. ‘It would make a useful little present for somebody.’ But who? she wondered, and then she realized, why, Miss Lord, of course. It was just the kind of thing she liked; indeed, she probably had one already. ‘I’ll have it,’ she said, handing over half a crown.

‘I’ll just put a bit of paper round it for you,’ said Marjorie, fumbling with a sheet of blue tissue paper. ‘Oh, dear, his little head is poking through — the ears make it difficult to wrap.’

‘It will go in my handbag,’ said Dulcie, ‘so please don’t bother.’

‘Oh, will it?’ Marjorie went on struggling ineffectually with the paper. ‘Perhaps that would be best.’

As Marjorie handed over the partially wrapped donkey Dulcie noticed that she wore a gold wedding ring engraved with a design of little flowers. Her fingers were rather stubby, with childish-looking short — perhaps bitten? — nails. It suddenly occurred to Dulcie that Aylwin Forbes had married beneath him — but why?

Crampton Hodnet

Crampton Hodnet Quartet in Autumn

Quartet in Autumn No Fond Return of Love

No Fond Return of Love The Sweet Dove Died

The Sweet Dove Died Excellent Women

Excellent Women A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym

A Very Private Eye: The Diaries, Letters and Notebooks of Barbara Pym Jane and Prudence

Jane and Prudence A Glass of Blessings

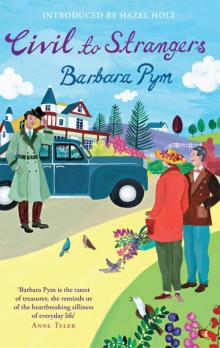

A Glass of Blessings Civil to Strangers and Other Writings

Civil to Strangers and Other Writings An Unsuitable Attachment

An Unsuitable Attachment Less Than Angels

Less Than Angels A Few Green Leaves

A Few Green Leaves Civil to Strangers

Civil to Strangers